PCUC | Pregnancy Resources and Information for Southwestern PA

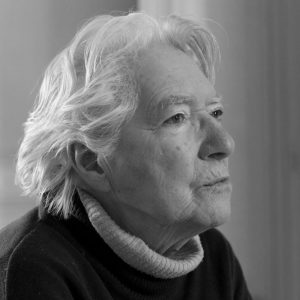

Meet Dr. Marthe Gautier

The Scientist who Discovered Trisomy 21 (Down Syndrome)

by Randy Engel*

Randy Engel: Dr. Gautier, before we begin this interview, I want to thank you for recommending to me the remarkable book by Professor Peter Harper of Cardiff University, Wales, First Years of Human Chromosomes – The Beginnings of Human Cytogenetics, which documents the groundbreaking efforts of scientific and clinical pioneers like yourself, in the field of genetics, from 1955 to 1960.[1] Professor Harper’s work, as well as his archived interviews, are a treasure trove of information regarding the history of human cytogenetics.

Randy Engel: Dr. Gautier, before we begin this interview, I want to thank you for recommending to me the remarkable book by Professor Peter Harper of Cardiff University, Wales, First Years of Human Chromosomes – The Beginnings of Human Cytogenetics, which documents the groundbreaking efforts of scientific and clinical pioneers like yourself, in the field of genetics, from 1955 to 1960.[1] Professor Harper’s work, as well as his archived interviews, are a treasure trove of information regarding the history of human cytogenetics.

Now, Dr. Gautier, would you be so kind as to give our readers some personal information about your family’s background?

Dr. Marthe Gautier : I come from an old family. We are French and Catholic and have always lived in the same area, the Île-de-France region, not far from Paris. We can trace our ancestors back more than 400 years. Originally our family was known for its “barbers and surgeons.” But many years later, one of my ancestors married a farmer, so we became farmers.

RE : You are the fifth of seven children ?

MG : Yes. I was born on the 10th of September 1925. My parents had four girls and three boys. Two brothers became farmers, two of my sisters married farmers, and the youngest of my brothers became a veterinary surgeon and married a pharmacist.

RE : But I understand that of the four girls, your elder sister, Paulette, became the first member of your family to attend medical school and that you followed in her footsteps?

MG : Yes, I joined her in 1942 at the Faculty of Medicine in Paris.

RE : At what point did you decide to specialize in pediatrics?

MG: I always wanted to be involved in the care of children. I knew that if there was any chance of my success in the medical profession, it would be in the field of pediatrics.

RE : Before we go into your early medical background, Dr. Gautier, I wonder if you could explain to our readers the various stages of medical studies in France, at the time you entered medical school.

MG: Certainly. The first step in becoming a Doctor of Medicine (an MD) was the entrance examination, the difficulty of which varied from year to year, followed by six years of clinical training, with a written examination each year.

For applicants wishing to follow the competitive examination route, which was the case for my sister Paulette and me, this pathway involved one competitive exam after another, each providing access to the next level and another step towards the responsibility of caring for patients. Externship was the first grade attained, followed by an internship of four years, at the end of which the candidate wrote a thesis. At each stage, the number of applicants admitted decreased.

Having reached this point, the candidate had to decide if he wanted to work towards clinical practice, (“chef de clinique”), a post-graduate grade which included the teaching of clinical medicine to students for a period of 1 to 3 years. This charge was very important as it could often lead to a university career. I also sat for a competitive exam to become a medical assistant. The final step was the so-called “médicat” exam necessary to become the head of a department.

I successfully negotiated all these steps up to the médicat. Women rarely advanced to this level at this time in history, although it is no longer the case today.

RE: Was the career pathway different for a candidate who wished to specialize in medical research?

MG : Yes, although I am less acquainted with the particulars. One did not have to be an MD, although some were. I know there were Commissioner exams each year at which time the publications of the candidates were reviewed to see if he or she should be promoted to research trainee, or researcher, or advance upward to several intermediate grades. Few reached the master of research level or went on to become director of research and head of a laboratory.

RE: Thank you for this information, the importance of which will become manifestly clear, later in this interview. Let’s return now to your own medical career. You told me that your competitive examination for internship was very difficult. Can you elaborate?

MG: Well, since this was the only way to reach the higher levels and open the door to a professorship or department head, I had to persevere. The written examination test papers were labeled only with an identification number, with no name, to ensure anonymity and to prevent favoritism or sex discrimination. However, this was impossible to avoid in the oral examination. Anyway, I succeeded at my fourth attempt. I was 25 and it was in 1950. That year, only two women became interns in Parisian hospitals, versus eighty men. This provided me with four years of experience in eight different pediatric departments. That meant eight different bosses working in different specialties and with very different teaching practices. It was a wonderful experience.

RE: I understand that before Paulette’s untimely death when German troops were retreating from Paris in 1944, at the war’s end, she gave you some excellent advice on being a woman in a male profession.

MG : You have to remember that when I arrived in Paris, during the war, from the country, I was only 17. I was completely naïve, my entire education having taken place in a Catholic girls school. In any case, Paulette was very adamant about two things. Firstly, she said that girls have to work twice as hard as boys, because we need to be especially brilliant in oral examinations, when we are the most vulnerable because our sex is evident. Secondly, nepotism was as rife in medicine, as it was elsewhere. Our father was a farmer and we had no relatives in the medical profession. So we had no highly placed contacts among the heads of departments who could help us.

We knew we were not the “bosses’ daughters,” but felt this was no reason not to try and reach the top of our profession. We knew it was a gamble. But of course, we did not reckon with my sister’s untimely and tragic death.

This is my own personal story which I am telling you today, but I think it bears witness to the veracity of my sister’s convictions concerning the role of women in medicine in the mid-20th century.

RE: How was it that you came to the United States to study at Harvard Medical School in Boston?

MG : During my four-year apprenticeship, I was privileged to be a protégée of the renowned pediatrician, Professor Robert Debré of the Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital in Paris. I completed my MD thesis titled “Fatal forms of rheumatic fever in children” in his department. My study focused on the clinical and post mortem anatomy and pathology of the heart affected by rheumatic fever. As it turned out, my one-year scholarship was funded by a friend of Prof. Debré, whose 10-year-old child had just died from severe acquired heart disease.

RE: Can you tell me about your work at Harvard?

MG : My stay in Boston was well organized by Prof. David Rutstein, Professor of Preventive Medicine at Harvard Medical School and a personal friend of Prof. Debré. Whilst there I also regularly visited the cardiology unit of Children’s Hospital under the direction of Dr. Alexander Nadas, a renowned pioneer in the diagnosis and surgical treatment of congenital heart diseases in neonates. I also was able to travel by Greyhound bus to six different medical centers in Cleveland, Chicago, Seattle, San Francisco, Washington and New Orleans, all specializing in the treatment of rheumatic fever in children – but all using different techniques and therapies. I gained invaluable experience from these visits especially since as a result of the war, Europe had fallen behind in this area. Of course, I enjoyed getting to see the wonderful American countryside.

RE: That sounds like a very full schedule. How were you able to also take on the task of working as a technician in the tissue culture laboratory ?

MG : For me, it was a pleasure. It was only part-time, mainly Sundays and holidays, and it enabled me to socialize. There was already an excellent technician working in the lab and she taught me to take and to develop photographs of cells which were obtained from heart or aorta specimens, following surgical interventions. She even taught me a little American slang.

The culture technique was very precise, but simple, provided you had all the necessary ingredients for the culture medium ready in the freezer. I also helped keep files up to date and acted as a liaison for the biochemists who were attempting to analyze the amounts and types of cholesterol in cells from explants (living tissue used as a medium for tissue culture) and patients of different ages.

RE: So it was all about biochemistry during that period?

MG : Yes, we never got involved in genetics or chromosome work.

RE: What happened when you returned to Paris in September 1956?

MG : Unfortunately, the position I was promised when I left for the United States had already been filled in my absence, and I had to find another position rather quickly. Prof. Debré had retired. I finally found an opening at Armand Trousseau Children’s Hospital, and I took it. I really had little choice.

My new boss was Professor Raymond Turpin, head of the Pediatric Unit at Hôpital Trousseau, who I later learned had a long-time interest in human and medical genetics especially Down syndrome, also referred to then as “mongolism.”

RE: I read about Prof. Turpin’s work in Prof. Harper’s book on the early history of cytogenetics. Turpin had introduced the teaching of genetics at the Faculty of Medicine in 1941 and established the Institute of Progenesis in 1958. I found it interesting that as early as 1937, he had proposed the possibility that Down syndrome may be caused by a chromosome abnormality. Had you known Prof. Turpin prior to your employment at Hôpital Trousseau?

MG : No, and this is an important point. I was never his protégée, or his “extern,” or his ” intern”. We were essentially strangers when I joined his pediatric unit for one year of “clinicat ,” which, as I explained earlier, was the teaching of clinical medicine to students. I found him to be an uncommunicative person, conscious of his superior grade. He had never been on good terms with my mentor Prof. Debré, and, moreover, I was a woman.

RE: When you first came to Hôpital Trousseau did you have any special interest in the field of genetics?

MG: No more than any other pediatrician. For myself, I was focused on the etiology of congenital heart disease.

RE: How was it then that you came to join in the international race to discover the genetic basis of Down syndrome ?

MG: It was really simply a matter of being at the right place at the right time.

The year was 1956, and Prof. Turpin had just returned to Paris from a historical meeting of the International Human Genetics Congress in Copenhagen, Denmark at which the number of human chromosomes was correctly established at 46, not 48, as had been previously taught.

I listened to him lament the fact that France lacked modern tissue culture laboratories and specialized equipment, which were available in other countries like the United Kingdom and Sweden, where the race was on to discover the cytogenetic cause of genetic disorders. Curiously, it was an area which had produced little excitement or interest among American researchers.

As he spoke, it struck me in a rather negative way, that here was a man who had proposed a genetic hypothesis for Down syndrome nearly 20 years before, and yet he had not gone on to pursue his theory. Most of Prof. Turpin’s genetic work now centered upon statistical data and dermatoglyphics, the scientific study of fingerprint patterns. Unusual dermatoglyphic patterns are related to chromosomal disorders such as Down syndrome and Turner syndrome. [2]

RE: So you spontaneously decided to jump into the fray and volunteered to establish a small laboratory on the hospital grounds with the idea of being the first to demonstrate the chromosomal number associated with Down syndrome – whether it be normal or abnormal? That’s amazing !

MG: Well, I already had experience in tissue culture, which is very simple. I also knew about the staining of pathology preparations. Obviously adaptation would be required, but I was eager and determined.

RE : What about medical supplies and funding under post-war time conditions?

MG: I was provided with a free laboratory space in the Parrot building so I did not have to worry about water, gas and electricity, and there was also a fridge, a centrifuge and an empty cupboard, but that was all.

Initially, I worked alone. There was no funding. So I took out a loan to purchase the necessary equipment and supplies, some of which were not even commercially available in Paris. Unfortunately, unlike the wonderfully equipped research facilities at Harvard, this ex-lab had no light microscope available to take pictures of my slides, only a low-definition microscope.

For some months, I was left to my own devices and I forged ahead.

With my loan I was able to purchase the glassware I needed. I used plasma from a cockerel that I bought in the country and housed on hospital grounds near the nurses’ quarters. This made it possible to obtain serum with a low calcium content for tissue culture. I also used 11-day-old incubated chicken eggs for embryonic extracts. These I obtained each Saturday from the Pasteur Institute, where my boyfriend worked. The human serum was my own.

RE : Did you undergo some additional study and training at the Sorbonne in cell biology, to help you perfect your technique especially for the staining of DNA?

MG: I did. As it turned out, I had problems with the initial stain techniques developed by Feulgen which did not work well under my old light microscope. It was difficult even to count chromosomes and the technique was not compatible with the sensitivity of photographic films in use at the time. Eventually, however, I was able to modify the procedure by incorporating the use of Giemsa stain, which is dark blue and that proved entirely satisfactory.

RE : Were there any problems related to contamination ?

MG: If you are referring to bacterial contamination, the answer is no. My experience in tissue culture at Harvard had taught me how to manage sterile cultures. Everything – my neutral glassware, the chicken embryo extract, the chicken plasma, the human serum – all were ecologically prepared.

What did worry me, however, was the possibility of chromosomal modifications due to long-term culture in vitro that might lead to “transformation” or alter the integrity of the karyotype. This did not occur, thank goodness, and in the end I was able to obtain chromosomes in prometaphase (the stage of mitosis or meiosis in which the nuclear membrane disintegrates), that were long and easy to count and pair off.

I was young. I was confident. And I had plenty of moral support from my boyfriend. I was far away from imagining what was to follow.

RE : Did Prof. Turpin visit your makeshift laboratory in the early days of your investigation?

MG : No, but I did receive sporadic visits from Docteur Jacques Lafourcade, his assistant, who presumably reported back to his boss on the progress being made.

RE : And you also had another regular visitor who seemed intently interested in your project?

MG : Yes, Dr. Jérôme Lejeune. He was in charge of the outpatient clinic for Down syndrome patients at the hospital. He was a researcher, first grade, working under the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), the largest governmental research organization in France.

We were about the same age, in our early 30s. I had not known him previously.

Later, I learned that he was a protégé of Prof. Turpin and that the two men, both pediatricians like myself, had collaborated on joint research projects and publications on dermatoglyphics and ionizing radiation studies in connection with suspected genetic disorders.

At first I did not pay too much attention to his visits. You have to understand that I was preoccupied with my own work on congenital diseases of the heart and I was just starting a private practice. In addition I had my teaching responsibilities as part of my “clinicat.”

RE : Did Dr. Lejeune have any skills or training in cell culturing?

MG : None whatsoever. As I noted earlier, Dr. Lejeune’s main interest was statistical data in connection with fingerprint patterns [dermatoglyphics] of children with Down syndrome. He had never taken an interest in pathologic studies or in cell cultures.

RE : Now let’s turn to the months leading up to your discovery of the genetic origin of Down syndrome.

MG : By July 1957, I had already set up my first normal cultures using control samples obtained from a surgeon operating on children without congenital abnormalities, with all the necessary permissions, of course. I preferred to use the fascia lata, the dense connective tissue that surrounds the thigh muscle. I continued the subculture of one of these samples for six consecutive months and the number of chromosomes was always the same: 46 chromosomes. I therefore assumed that my technique was working perfectly.

Then I asked Prof. Turpin to provide me with a sample from a patient with Down Syndrome DS patient for culture, again with the necessary permissions. I was feeling quite proud of myself at having made so much progress since my return from the United States.

Unfortunately, for reasons that I do not understand, even till this day, the critical tissue sample I requested from Prof. Turpin did not arrive until May 1958. A silent gulf had developed between us that made communication difficult. I was contemplating giving up on my efforts when the fragment of tissue finally arrived.

I counted 47 chromosomes on the first mitoses I obtained from the Down syndrome sample thus revealing the first autosomal chromosome aberration recognized in the cells of the human species – trisomy 21. [3]

However, I didn’t have a photo light microscope to identify the 47° small fragment.

RE : Was that when Dr. Lejeune offered to help?

MG: Yes, without a light microscope I could not take photographs of my discovery. Dr. Lejeune volunteered to take my slides to another laboratory and get them photographed. Naïvely, I consented. This was in June 1958. Only much later was I told that the slides of my discovery were first photographed in Denmark, the homeland of Madame Lejeune, while the family was on holiday. A local Danish paper carried the story.

RE: Did he ever return the slides with the promised photos to you?

MG: No, never. I never saw them. When I finally asked him where the slides were he told me they were being kept under lock and key by Prof. Turpin.

RE: Tell me about the meeting of the International Human Genetics Conference in Montreal, Canada held in August 1958?

MG: Dr. Lejeune was there as an expert on ionizing radiation representing the CNRS. But he also had in his possession a large amount of data relating to my investigation which he had taken without my knowledge.

Lejeune requested that an informal seminar of geneticists be organized at the Department of Genetics at McGill University at which time he proceeded to announce the discovery of the presence of an additional piece of chromatin in patients with Down syndrome.

RE: Did he mention your name in connection with the discovery?

MG: No. He presented the findings as if they were his own. Henceforth, the discovery would always be associated with his name.

RE: I see. So your discovery launched his career. What was the audience’s reaction to Lejeune’s announcement at McGill University?

MG: I was told it was a mixture of excitement and skepticism. But the important thing was Lejeune had let the cat out of the bag, so to speak.

RE: Did you know anything about these events which were unfolding concerning your discovery?

MG: No, not at the time. Drs. Turpin, Lafourcade and Lejeune managed to kept me isolated and uninformed. Again, I was too young and naïve to understand the nature of the political game being played out.

Then, in the fall of 1958, I received a letter dated November 5, from Dr. Lejeune, who was in the United States visiting various Drosophila laboratories. The common fruit fly had been used in experimental genetics since 1910.

He wrote to inform me that he had received a letter from Prof. Turpin stating that a Norwegian professor had visited the hospital to see my wonderful slides.

RE: What happened when Dr. Lejeune returned to France?

MG: Without any consultation with me, Drs. Lejeune and Turpin arranged to publish the details of my scientific discovery of the first human chromosomal abnormality in the Comptes Rendus, the French Academy of Sciences’ official publication in Paris, within three days. This gave our laboratory an advantage over the English teams also racing to identify the cause of Down syndrome because other international journals normally took two months or more to report on new scientific discoveries.

RE: At what point were you brought finally brought into the picture?

MG: The prepared text was read to me by Dr. Lejeune at midday on Saturday, January 24, 1959, for presentation the following Monday. January 26. At this point I was suddenly awakened from my slumber. I was in shock!

RE: But more shock was on the way when the Comptes Rendus, arrived that Monday, n’est-ce pas?

MG: Absolutely. Contrary to standard professional practice, Lejeune’s name appeared in first place as the senior author of the paper, followed by my name, and then that of Prof. Turpin. Thereafter, the citation read, Lejeune et al. 1959. And to add insult to injury, my last name was misprinted “Gauthier” instead of “Gautier,” and my Christian name “Marie” instead of “Marthe.” I still don’t know whether that was done on purpose or whether it was simply a typographical error.

This initial article, (Lejeune J., Gauthier Marie, and Turpin R. (1959), “Les chromosomes humains en culture de tissues,” (C.R. Acad. Sci. 248, 602-603, 26 Janvier 1959) was very short and limited in scope, but it was to pave the way for a new discipline – human cytogenetics. [4] It purpose was simply to establish the Paris group as the discover of the autosomal chromosome abnormality in children with Down syndrome.

Two additional papers followed in the March 1959 issue of Comptes Rendus. These covered nine cases of children with Down syndrome, all of whom bore the extra 47th chromosome.

A fourth paper, complete with additional photomicrographs showing the chromosome preparation and karyotype was later published in the Bulletin of the National Academy of Medicine ( Lejeune J., Gautier M., and Turpin R. (1959), Le mongolisme, maladie chromosomique, Bull. Acad. Natl Med, 143, 256-265.)

In this way, Lejeune put himself forward in the media spotlight as the discoverer of the extra chromosome in Down syndrome, when, in fact, he actually had nothing to do with the discovery.

RE: So Lejeune accepted honours not due him, but due to another – a young woman named Dr. Marthe Gautier. Did he later attempt to rectify this “oversight,” by publicly recognizing you as the discoverer of the extra chromosome in Down syndrome?

MG: No. Never. In 1962 he was honored in Washington, D.C. by President John F. Kennedy with the first Kennedy Prize for his “discovery of the cause of Down syndrome,” and in 1969 he received the William Allen Award of the American Society of Human Genetics, the highest award possible for a geneticist, without acknowledging me in any way, and certainly without sharing any of the prize money.

I think that Lejeune (and Turpin) developed a sort of “disease” well known among scientific researchers called “Nobelitis.” He seemed sure that he and Turpin would win the Nobel Prize, but they needed to eliminate me because the Nobel Committee could not award the prize to three people from a single laboratory. In the end neither won the coveted prize.

Interestingly enough, when my new laboratory with additional staff and equipment was set up after the discovery of the Down syndrome karyotype, a film was made in which I appeared at the beginning explaining the technology and peering over my microscope. Two years later, I happened to see this film again. My image had disappeared, only to be replaced by that of Lejeune.

In the end, I understood that it was impossible to deal with such people.

Lejeune and Turpin continued to publish papers on trisomy 21, and my name was gradually eliminated from the list of authors.

Eventually, even Prof. Turpin’s name was dropped from their papers as Lejeune came to be viewed the world over as the discoverer of the extra chromosome in Down syndrome. The heirs and family of Prof. Turpin were eventually forced to take legal action on the matter. Lawyers for the Turpin family produced evidence from the archives of the Pasteur Institute archives documenting Turpin’s seniority in the chromosome-based hypothesis concerning “mongolism.” His achievement was finally verified and recognized on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the discovery of the cause of Down syndrome in 2009.

RE : I recall that you once said, “I have no happy memories of that period, as I felt cheated in every respect.”

MG : Yes, I remember. But in the end, I made the decision to return to my first love. All of my early medical career had been spent in categorizing pediatric congenital heart diseases. Now I wanted to devote my life to helping children suffering from these ailments. I never regretted that decision.

So, after I had completed my “clinicat” at Hôpital Trousseau, I took a position at Bicêtre Hospital in the south of Paris, as an assistant in the Department for Infants specializing in congenital heart problems. Later, I assumed clinical responsibility for the department.

Actually, I spent the rest of my medical career at Bicêtre Hospital even when I went to work for INSERM and while I was also engaged in home clinical practice.

RE : When did you join INSERM? (French National Institute of Health and Medical Research Institute).

MG: I joined INSERM as Director of Research in 1967. It is connected to both the French Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Higher Education and Research. I was asked to create a tissue culture subdivision designed for work on fibroblasts of other congenital metabolic abnormalities such as those concerned with fructose or galactose intolerance.

In this way my whole life became devoted to the study of congenital mechanical and metabolic abnormalities in infants and children.

RE : When did you retire from medical practice ?

MG : I retired at the legal age of 65. At that time, the Director of INSERM wanted to put my name forward for the “Légion d’honneur.” I refused. It was too late. I would have accepted it in 1959, but not now. I was given a wonderful microscope with phase-contrast and fluorescence modes as a retirement gift. I sent it to a pneumology department in Vietnam that needed it very badly.

I am happy to report that a commemorative plaque has been installed and unveiled at the Hôpital Trousseau in recognition of the discovery of the cause of Down syndrome. I was invited to be present at the ceremony. My name is the first one on this plaque.

RE : I know that you have developed an extraordinary talent for painting pictures of flowers from your village, on paper and on porcelain. Your work is exquisite. Simply beautiful. Do you have any other passions which you are pursuing in your retirement years?

MG: My Herbarium, for one. And recently I started to work on the genealogy and story of our large family in order to pass on our history to future generations. My parents lived through two wars against Germany. We live differently now and there has been many dramatic changes. I would like to record these changes for posterity.

RE : A have a couple of final questions for you if you will bear with me.

I understand that in 2009, on the 50th anniversary of the discovery of Trisome 21, you were encouraged by Prof. Simone Gilgenkrantz and Dr. Peter Harper to set the record straight on the circumstances surrounding that discovery. What made you break your silence after so many years?

MG : Both are geneticists and now historians of medicine, and of genetics in particular. They wanted to know more. And for the first time, I felt willing and able to enlighten them on the circumstances surrounding my discovery. In March 2009, I shared a wonderful anniversary celebration with them and other good friends in my Paris home. I am grateful to have such wonderful friends with whom I can share my end years.

RE : I understand that you and Catholic pediatrician Dr. Jacques Coureur and other concerned French Catholics have prepared and filed letters and documents with the postulator for the cause of beatification of Dr. Lejeune at the Vatican, concerning the events surrounding your discovery of the cause of Down syndrome. Has the evidence you have submitted to the Congregation for the Saints been acknowledged yet?

MG : As yet, Dr. Coureur and I have received no such acknowledgement. I do know that the postulator Dom Jean Charles Nault from the Saint Wandrille Abbey is responsible for the case and that he is has to provide Rome with documents both in favor and against the beatification of Dr. Lejeune.

RE: In his Commentary on “Fifty years of human chromosome abnormalities,” Prof. Harper wrote, ” …the widely perceived role of Dr. Jerome Lejeune as the discoverer of trisomy 21 requires revision, preferably also in light of other evidence and documentation… .” [5]

“Regardless of the significance of Lejeune’s own contribution to the discovery of trisomy 21, there can be no doubt as to his key role as the leader of the Paris school of human cytogenetics, which over the following decade made a series of major discoveries of human chromosome abnormalities … . ” he states. [6]

Harper also acknowledges that “the initial publication concerning a major scientific discovery may not always contain the full truth, especially when this concerns the relative contribution of those involved. It is salutary to note that it may take 50 years or more for all the facts to come into the public domain… .” [7]

I thank you for the privilege of this interview, Dr. Gautier, and for the opportunity to make your pioneer achievement in the field of genetics better known in the United States. You have made a distinguished career in the field of pediatric cardiology. May your golden years be filled with much joy and peace.

MG : Thank you. I would like to complete this interview with a picture of the presentation of the Winslow Prize offered by Novo Industry for the discovery of trisomy 21 as the chromosomal basis of Down syndrome . The reception was held at the Danish embassy in Paris in December 1971. I am here with Prof. Debré who organized the event on my behalf.

NOTES:

*NOTE: Randy Engel is an Advisory Board member of PCUC.This interview originally appeared on RenewAmerica.com on March 26, 2013: http://www.renewamerica.com/columns/engel/130306